Although we enjoy the lighter side of early mediaeval life – board games, chanting psalms, visits from the Bishop and so on – life in Anglo-Saxon England was hard and there were many ways in which a person might find themselves in slavery. As part of our exploration of monastic life, we present a draft manumission document.

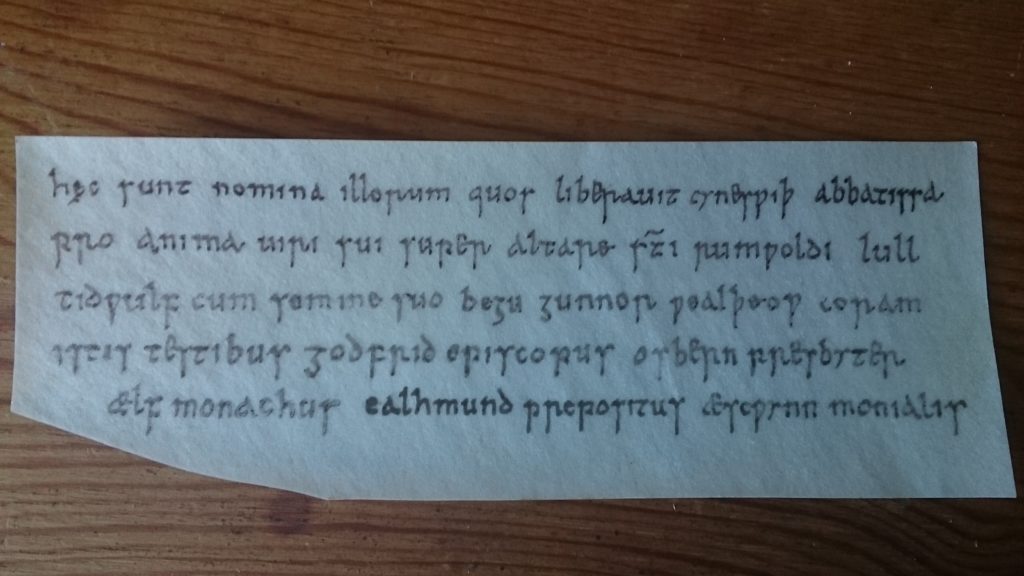

This is a manumission document, a record of slaves being freed. Written on real parchment, the text is in Latin but written in an insular hand.

Translation

These are the names of the people whom Abbess Cyneswithe freed for the soul of her husband, at the altar of St Rumwold: Lull, Tidwulf and his offspring, Begu, Gunnor and Wealtheow – in the presence of these witnesses: Godfrid, bishop; Osbern, priest; Ælf, monk; Ealhmund, reeve; Æscwynn, nun.

Text (in Latin)

haec sunt nomina illorum quos liberavit cyneswith abbatissa

pro anima viri sui super altare sancti rumwoldi lull

tidwulf cum semine suo begu gunnor wealtheow coram

istis testibus godfrid episcopus osbern presbyter

ælf monachus ealhmund prepositus æscwynn monialis

This is a draft manumission document, recording the occasion when Abbess Cyneswithe freed five of her slaves as an act of charity, dedicated to the redemption of the soul of her deceased husband. The manumission took place at the altar of the monastery chapel, witnessed by local clergy, the monastery’s reeve or steward, and one of the senior nuns. The manumission was written into the monastery’s gospel book so that the freed slaves could be sure of being able to provide proof of their free status.

Lull was an elderly ploughman, born into slavery and brought up with Cyneswithe’s husband.

Tidwulf had committed a crime against Cyneswithe’s husband, and when he wasn’t able to pay the fine that was the punishment for his crime, he was enslaved for the debt. While Tidwulf was a slave he married and had children. After the death of his wife, Cyneswithe freed him and his young children, allowing Tidwulf to return to his original place in local society.

The three women freed will enter the monastery with a status something like later lay sisters, servants living a religious life.

When Begu was a child, she was sold into slavery by her poverty-stricken family. This allowed her family to gain some money, to save the cost of her upkeep, and to ensure that she was fed and clothed – though at the cost of her freedom.

Gunnor was a Viking girl, captured after an English army took over the place where her family lived.

Wealtheow was a Welsh woman, kidnapped in a raid over the border. A slave trader took her to the other side of England to sell her. Her new owners didn’t bother learning her Welsh name and just called her Wealtheow, which means ‘Welsh slave’.

Fact versus fiction

Rumwoldstow is fictional and so is this manumission and its story – but the document is based on surviving manumissions found in Anglo-Saxon gospel books, and the stories about the slaves relate to what is known about Anglo-Saxon slavery.

People became slaves in various ways. Some were born into slavery; it seems likely that slave status came from the mother. In a charter of 902 a group of six slaves were listed as part of an estate’s assets – three of them were described as being of slave birth.

In warfare, women and children were taken captive and enslaved. So, for example, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records the attack on the Viking fortress at Benfleet in 894 and describes how the English army seized the women and children and took them to London. The Chronicle for 1055 describes how the exiled Earl Ælfgar attacked Hereford and enslaved a large number of the city’s inhabitants.

Women and children were also enslaved in smaller scale slave raids or were kidnapped. They were removed from their home area and sold somewhere a long way away. For example, a northern slave woman was kidnapped from her master and ended up in Winchester. Wealthy kidnapped people might be ransomed, but poorer people would be sold into slavery.

The profit from taking women and children as slaves was a particularly valued part of the plunder from warfare and raiding. And women slaves of any origin were likely to suffer from sexual violence and exploitation.

Slaves could be bought at any market town. One tenth century source shows how slaves were valued compared to agricultural animals: 30 shillings for a horse, 20 shillings for a person, 1 shilling for a sheep.

People could become slaves through poverty, because of unpaid debts or by selling themself or a family member into slavery. King Alfred wrote about fathers selling their daughters into slavery and there was an Anglo-Saxon law allowing the sale of sons under the age of seven, or over the age of seven with the consent of the son. There is a manumission which refers to people selling themselves into slavery – their owner freed the people ‘whose heads she took in exchange for food in those evil days’.

A common form of debt that resulted in slavery was the inability to pay the wergild or compensation due as punishment for a crime. If someone was convicted of a crime and they couldn’t raise the money to pay the wergild, they became the slave of the person they had wronged.

These penal slaves were the most likely to be freed: there was a stronger moral imperative to return these slaves to their place in the local community. For example, in her will the 10th century Wynflæd asked her children to make sure that all her penal slaves are freed.

Freeing slaves was seen as a pious act of charity towards those who were most unfortunate. Slaves could be freed on condition that they performed some future service, particularly praying for the souls of deceased owners. For example, the 10th century will of Æthelgifu freed three women on condition that they sing the psalter for a year in memory of her and her husband.

Slaves were more likely to be freed when they were less economically important – the youngest and oldest were chosen to be freed. For example, Æthelgifu’s will provided for freeing Dufe the Old, and for freeing some slaves with their children, but some young adult slaves were bequeathed to new owners.

Anglo-Saxon literature often expresses contempt for slaves – one of the Exeter Book riddles refers to a Welsh slave woman, dark-haired, foolish, drunken and wanton. However, the riddles also deal with the suffering of captivity and servitude in more complex ways and give a voice to objects identified with slaves. Ælfric in his Colloquies explicitly describes the experience of slavery: the slave ploughman says ‘The work is hard, because I am not free’.

Bibliography on early medieval slavery

R. M. Karras, ‘Desire, descendants and dominance: slavery, the exchange of women, and masculine power’, in The Work of Work: Servitude, Slavery and Labour in Medieval England, ed. A.

J. Frantzen and D. Moffat (Glasgow, 1994), pp. 16–29

Gillingham, John. “Women, Children and the Profits of War.” In Gender and Historiography: Studies in the Earlier Middle Ages in Honour of Pauline Stafford. Edited by Janet Nelson, Susan Reynolds, and Susan Johns, 61–74. London: Institute of Historical Research, 2012.

Paolella, Christopher. Human Trafficking in Medieval Europe : Slavery, Sexual Exploitation, and Prostitution. Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2020. Social Worlds of Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages.

Pelteret, David Anthony Edgell. Slavery in Early Mediaeval England : From the Reign of Alfred until the Twelfth Century. Woodbridge: Boydell, 1995. Print. Studies in Anglo-Saxon History, 7.

Rio, Alice. Slavery After Rome, 500-1100. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Wyatt, David. Slaves and Warriors in Medieval Britain and Ireland, 800–1200. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2009.