The mantle is one of the most characteristic and yet mysterious of early mediaeval garments, one that seems to be a woman’s garment. You can read the beginning of my adventures with the mantle in earlier posts:

Mantlepieces

Pin the mantle on the nun

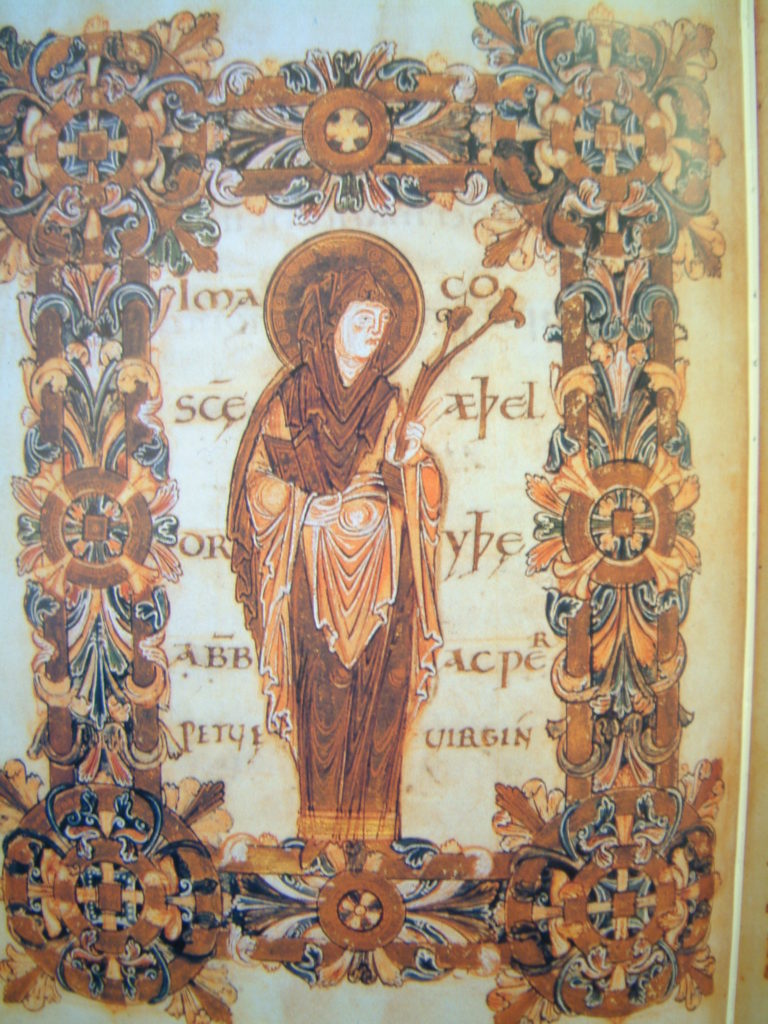

We have no archaeological evidence for the mantle, only literary references and manuscript illustrations such as the picture below showing Saint Æthelthryth.

Source: By monk – [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=32907989

I’ve now completed two versions of the mantle – one for every day, and one for high days and holidays.

The plain mantle

My plain mantle is a semicircle of grey wool, hemmed around the curved edge, and using the selvedge of the fabric along the straight edge. This is the same shape as an ecclesiastical cope.

The wool is a little scratchy and I very naughtily sewed a strip of nice smooth linen along the inside of the cloak where it touches my neck. A real nun would leave the wool plain and accept the discomfort. Honest.

The mantle in illustrations shows no opening, and for this version I sewed the front closed up to about my breastbone, so you put it on over your head. It’s a warm and comfortable garment, very cosy if you are working from home and it’s a bit chilly; it keeps one’s body and legs warm, and you can easily put your hands up under the front hem and I think this gives an appearance in keeping with the manuscript illustrations. The straight edge can be folded over to make a collar and it keeps the back of my neck warm.

Would an artist have drawn the seam down the front? Or would they have just drawn the overall shape, as we see it in illuminations?

For any serious labour, you would want more freedom of movement and I think that’s where the scapular (a tabard-shaped apron) would come into its own both for warmth and to protect your main garments from dirt.

The fancy mantle

I wove a decorative band to go round the neck of my fancy blue wool mantle which Abbess Cyneswithe will wear when there are posh visitors to Rumwoldstow, such as Bishop Godfrid (whether or not he is having an ascetic moment). The design for the tablet weaving is inspired by brocaded tablet-woven edges to the vestments of St Cuthbert (Durham textiles) and embroideries on the Llangorse Fragment, woven in a technique known from Laceby, Lincs and also one of the Durham textiles. Birds, clumsy lions and plants seem to have been familiar high-status motifs.

The band is woven in find wool, which I moistened and ironed to help ease it around the curve.

My blue mantle is a full circle and is open-fronted. I found that a light, ansate brooch is entirely adequate to close it – there is less weight on the pin than there would be with a heavy rectangular cloak. The front edges naturally overlap and are really very stable. And again, the opening is not, I think, very obvious.

This garment is even more snuggly than the plain mantle, being a soft, lightweight wool.

Both the plain and fancy mantles are high status garments as they are made by cutting away fabric and discarding it, to create a half or full circle.

The mantle is often reconstructed as a poncho with rounded corners, but the poncho design (a flat fabric with a hole cut in the middle) doesn’t seem to relate to cloaks from around this time, whereas the semi-circular cloak is known from finds such as Leksand and lived on in the ecclesiastical cope. The poncho could be regarded as a wider scapula with curved edges – it’s a totally valid interpretation – but I went with the half- and full-circles to see what they’d be like.

The circle has the advantage that you don’t have to put it on over your head. The half circle uses less fabric and keeps your neck warmer, also you don’t need a clasp. Both are good, warm, practical garments and I think fit the iconography well enough.